In life, people should rarely settle for second best, whether it be at work or in their personal life. Investing is no different, according to Mark Sherlock, manager of the Federated Hermes US SMID Equity fund, who has learned over time that price can be irrelevant if picking the clear-cut winner in a sector.

“Whenever I've bought the number two player from a quality point of view, it's never worked out. You should always buy the best quality you can,” he said.

“That’s because you either end up losing money or selling the number two to buy the number one, or certainly I do. So be cautious when buying lower quality.”

The manager highlighted provider of environmental and industrial services Clean Harbors as an example for a no-compromise stock, with “a wide economic moat due to the scarcity of their assets, ever increasing regulation and very limited new supply entering the market”.

Simple rules like this make his chances of outperforming much easier. Indeed, a rule of thumb is that fund managers need to only get slightly more than 50% of their portfolio right to make exceptional returns.

What managers are hoping for is that the payoff is hopefully high enough for the stocks that they get right to more than offset the losses when they draw a blank. After all, a stock can only lose 100% but can go up exponentially.

Never settling for second best is one trick up Sherlock’s sleeve. Another more idiosyncratic one is to be cautious about companies with significant exposure to the government.

“I'm pretty sceptical of investing in stocks with significant exposure to the government. I can think of at least two examples of stocks that haven’t worked because the government has rewritten the rules,” he said.

“You think there were particular barriers in place, but then a piece of government legislation changes the rules overnight and your barriers have eroded.”

One such case was Corporate Office Properties Trust, (now COPT Defence Properties), a company that owned offices around the Washington DC area.

“The offices were rented out to a number of government suppliers, particularly in the defence industry. The office company benefitted greatly from a rule according to which subcontractors to federal agencies had to be within a certain geographic radius of government buildings, which created very strong demand for a finite supply,” he explained.

“When the suppliers had to increase prices, because the expensive office space amongst other things, the 10-miles radius rule was binned and of course, instantly, the barriers were gone and so over time, rents fell away and people moved out. That was annoying to say the least.”

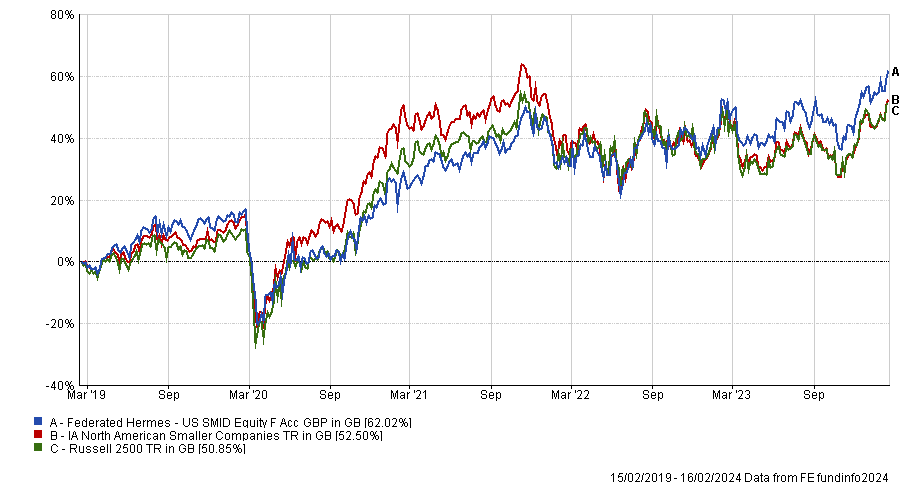

Implementing these two strategies has worked for Sherlock in the past five years, as the fund’s performance below testifies.

Performance of fund vs sector and index over 5yrs

Source: FE Analytics

Through his bottom-up process, the manager selects US small and mid-cap companies with “durable competitive advantage” that can generate “good compound returns” by losing less during downturns and outperforming during upturns.

His preference for small-caps is another way he can increase his hit ratio and make sure he could make more active decisions for his portfolio, as this is where research can prove invaluable.

“There are – plus or minus – 50 analysts covering large-cap companies such as Apple. Even with my arrogance, what can I add to that debate?,” he asked.

“Conversely, there are between zero and five regional analysts covering my market cap, so there's a lot more opportunity to add alpha.”

This also adds risks and when the manager tries to quantify the mistakes he made in his career, he said there are “so many”.

“Being a fund manager is quite a funny job. The market could be a very humbling place and yet, you're paid to have a view and clearly you think your view is the right view, otherwise you wouldn't be doing what you were doing.”

“It's weird. You have to have the confidence to back your ideas (and hopefully that doesn't trip into arrogance), but also have the appreciation that you could be totally wrong.”