Consumer goods companies could be a bellwether to ride out a recession despite shoppers having a tighter budget, according to a number of fund managers.

Some might assume these companies would be under particular pressure given how high inflation has caused consumers to spend less, but Tellworth UK Income and Growth manager Mark Barnett insisted this is not the case.

Inflation in the UK may be high, but it has done little to deter consumer spending. Nevertheless, the assumption that revenues will suffer has knocked down share prices “far too low,” allowing Barnett to swoop in and buy companies such as Whitbread and Premier Foods at large discounts.

“Despite much press commentary highlighting this wage squeeze combined with the pessimistic forecasts from the Bank of England and the IMF, the UK consumer has continued to spend and actually is fundamentally in pretty good shape with strong cash balances, low levels of debt and, high levels of employment,” he said.

“These buffers have provided a cushion against the recent shocks and will act as a springboard for the eventual recovery.

“We think this investment theme has further to run as the profit potential of these businesses has improved post-pandemic given the change in market structure which has occurred to the benefit of well capitalised, quoted businesses.”

These types of companies may be proving resilient, but Odyssean Investment Trust manager Stuart Widdowson was still cautious of consumer cyclicality, choosing to avoid the area altogether.

He said the will of the consumer is difficult to predict and can change rapidly, having sizable impacts on company earnings.

“You can have businesses that just swerve off when a creative director gets it wrong or if the world moves on and the business doesn't change,” Widdowson added. “Something can be all the rage and then just fizzle out.”

Despite holding almost a quarter of his portfolio (24%) in consumer companies, Fidelity European manager Marcel Stozel said he is acutely aware of the risks Widdowson mentions.

While he does think some consumer brands having strong pricing power, Stotzel said the majority of names in the sector fail to display durability.

“It's something that we're definitely very cautious on and it’s the exact reason why I didn’t buy Kering, which owns Gucci,” he said.

“I don’t know if it’s going to become one of those timeless brands where it doesn’t matter what it drops each season because people will just go out and buy whatever is there.

“There are only four companies in the world that are like that – Louis Vuitton, Hermès, Cartier and Dior are the only ones that have reached that timeless level.”

Although they are few and far between, the consumer brands with this “timeless” status have an appealing outlook over both the short and long term, according to Stotzel.

Even if lower consumer spending injures revenues in markets such as the UK, a surge in post-lockdown shopping in China could keep those companies afloat.

“Luxury goods companies are more immune to a consumer slowdown than most, but not entirely,” Stotzel said.

“The Chinese reopening play has almost become a bad word because it hasn't played out in the way people hoped, but luxury is one of the few areas where that definitely looks like it will play well over the next few quarters.

“Over a three-to-five-year time horizon, I don't see any reason why the long-term structural trend towards luxury spending should be anything different.”

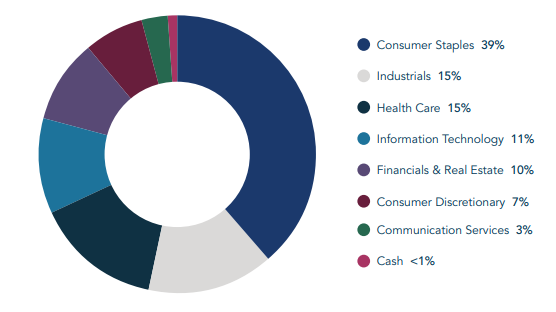

Tomasz Boniek invested almost half (46%) of the STS Global Income & Growth trust into consumer goods companies, but did say that not all brands are successful in retaining customers when prices get higher and budgets get tighter.

Sectoral allocations of STS Global Income & Growth

Source: Troy Asset Management

It is for this reason that he has held off buying companies such as Starbucks and EssilorLuxottica, which could be attractive additions to the trust if their consumers remain faithful.

“It is no secret that the consumer continues to be under a bit of pressure with a potential weakening labour market around the world and we wonder whether that is the case with Starbucks,” Boniek said.

“Coffee is good, but if you don't have a job, you're maybe not going to spend $6 every morning to buy your flat white.

“The same is true with EssilorLuxottica – it’s a very resilient product category that dominates the eyewear market globally, but if times are tough, you will perhaps spend less on some fancy RayBans.”

For the time being, Boniek said his “committed allocation to consumer goods” is “at the upper end of what he will want to have in that sector,” yet they have performed well in a challenging economic environment.

Consumers have proven to be extremely loyal to the brands they like, giving those companies the helpful ability to rise their prices above the rate of inflation.

“The market likes to write them off every few years but they just continue to do what they've always done for decades without ever missing a beat,” he said.

“People told us these businesses have no pricing power left, but that was because there was no inflation – now we have inflation back, we’ve seen some of these businesses exercising tremendous pricing power.”

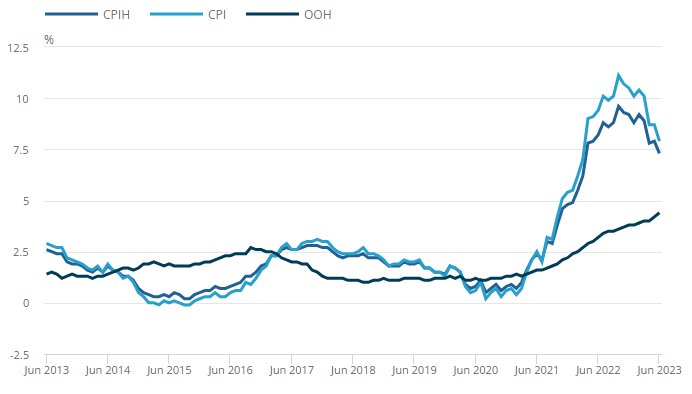

Although inflation remains above the Bank of England’s 2% target, it has dropped significantly from its 11.1% peak to 7.9% in June’s latest estimates.

UK inflation rates over the past 10 years

Source: Office for National Statistics

Many consumer goods companies have upped their prices accordingly and, now that inflation is on its way down, profit margins are far wider than they were prior to the cost of living crisis, according to Boniek.

“A debate is going on about whether growth will come down because you can’t put prices up whilst inflation is going down, which is particularly true, but then costs are also going down more than these companies have put prices up,” he explained.

“What we're therefore likely going to see is margin expansion that will allow these businesses to continue with that consistent earnings growth.”