Passive funds’ low ongoing charge figures (OCF) have made higher fees charged by active funds unpalatable and driven prices down across the industry but many still charge relatively high fees.

This can be acceptable if the manager is able to demonstrate risk-adjusted returns over and above the charges, according to experts, but there is a limit.

Meera Hearndon, investment director at Parmenion, said: “There cannot be any compromise over this. If this delivery of consistent outperformance does not exist, it becomes difficult to justify high charges.”

Yet, few active funds actually deliver for investors. Using the IA Global and IA UK All Companies as proxies, only 23% of global funds have beaten the MSCI World over 10 years and 29% of UK funds the FTSE All Share.

To assess whether higher fees are justified, Nick Wood, head of investment fund research at Quilter Cheviot, explained that a first element to identify is the expectation of alpha generation.

He said: “We have recently seen a number of funds that are seeking to be very low tracking error, generating limited excess return. In these cases, having a low OCF is key as every basis point of cost really impacts ability to outperform. Conversely, higher alpha generators, if they achieve that, have less of an issue.”

It is also important to take the asset classes into consideration, as some naturally attract higher fees than others. For instance, fixed-income funds are generally cheaper as a high OCF is more likely to hamper returns than with other types of assets.

David Morcher, head of collectives at Avellemy, said: “We would have a lower tolerance for paying a higher OCF in fixed income instruments, where the expected return profile is likely more muted than equities through the cycle and thus a high OCF might more greatly impact our net returns through time.”

Within equities, small-cap and emerging market companies are more expensive to research and trade, which means product providers will generally charge higher fees for funds specialised in those markets.

In theory, managers investing in these markets are more likely to generate alpha, so one would expect the outperformance to make up for the higher fees, but investors should bear in mind that those sectors do not always live up to their promises.

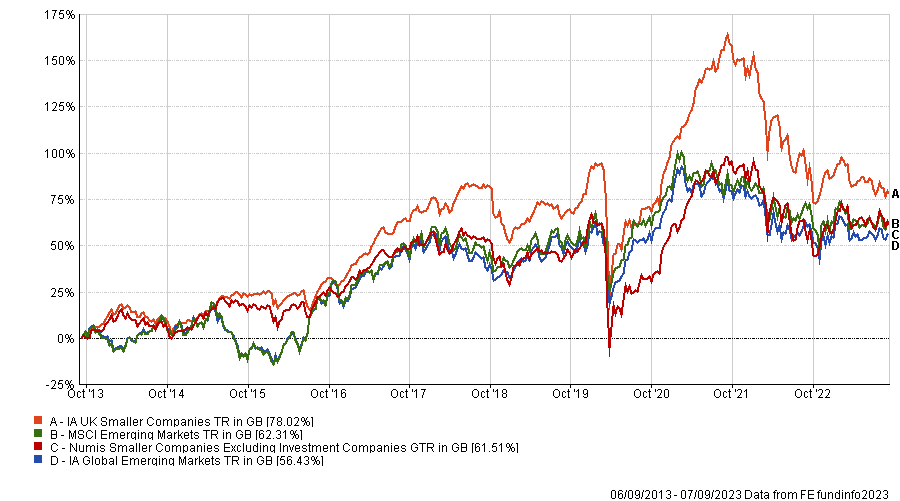

Kamal Warraich, head of equity fund research at Canaccord Genuity Wealth Management, said: “Not all strategies are created equal. For instance, the performance of UK small-cap funds has been very strong over the long term, so the fees might be justified.

“Conversely, emerging market funds tend to be relatively expensive and have not justified their fees on the whole for a variety of reasons.”

Performance of indices and sectors over 10yrs

Source: FE Analytics

Another example of funds charging higher fees are those investing in less liquid asset classes which require a higher level of costs to transact. That includes commercial property or infrastructure, where transactions from start to finish can involve many ad-hoc costs, such as agent fees, a raft of legal advice fees and stamp duty.

Morcher said: “If you want exposure to those markets, presumably in order to obtain some form of diversification from other more liquid assets, then you might have to accept that transacting in these markets comes with a higher cost than some more liquid markets. You would expect these costs to be passed on through the OCF.”

Hedge fund strategies also attract higher fees, often using a ‘two & 20’ structure – 2% for the management and 20% for the performance. Warraich warned, however, that they do not really justify their charging structures.

How much is too much?

A lot will depend on the asset class and the investor’s expectation of alpha generation. For instance, a manager of a core active equity fund charging higher fees but consistently outperforming the index and delivering value net of costs is less of an issue.

Yet, Wood said that any fund with an OCF in excess of 1% has to justify its place in a portfolio, whereas Hearndon suggested that any additional charge of 0.1% on the top of a 0.75% annual management cost is too much for a large-cap fund.

She added: “Fund managers need to be able to strike the right balance between being profitable and being fair. Excessive pricing shouldn’t be tolerated.”

Wood also noted that it is worth considering the fund’s underlying resource.

He said: “If this is a very small team and resource, is the extra cost really justified? Conversely, a well-resourced team will be much higher cost for the asset manager, so perhaps justifies this.”

Finally, investors should remember that cheaper does not necessarily mean better and shouldn’t exclude funds from their buying list just because of the higher fees they may carry.

If they are convinced of the quality of a management team, their ability to be disciplined in their investment processes and to deliver the long-term risk-adjusted returns on a consistent basis, then it could be reasonable to buy this fund despite the costs.

Wood also gave the example of private equity investment trusts, which have larger costs attached to them.

He said: “Whilst investors still need to be aware of excessive charging, the ability to access illiquid private investments which have provided strong returns after fees in the long term and with an element of diversification is something investors may want to consider.”