Investors should brace for high inflation to persist into next year if supply chain hold ups are not dealt with, according to experts.

Towards the end of 2021 the impact of higher prices was already being felt. Stocks wobbled while bond prices rose as central banks began taking measures to combat higher inflation, including raising interest rates and cutting back their asset purchasing programmes.

If this persists, growth stocks – such as the giant technology companies – should lag as these stocks are generally on higher valuations due to their future earnings prospects. When rates rise, however, these future earnings have a higher discount rate, reducing their appeal.

Similarly, bonds should also perform poorly, as higher interest rates should lead to higher bond yields and therefore lower prices.

Susannah Streeter, senior investment and markets analyst at Hargreaves Lansdown, said it is something investors should brace for heading into next year.

“The snarled up supply chains all over the world that have forced prices higher, don’t look set to ease significantly,” she said.

Guy Foster, chief strategist at Brewin Dolphin, said that production delays will be resolved and supply will catch up with demand, but not until the end of next year.

Until then, prices will continue to climb and central banks will be under increasing pressure to implement tighter monetary policies.

Inflation rates are currently well above central banks’ aims of 2%, leading to fears that increasing prices may lead to a mismanagement of monetary policy.

Streeter warned that the balancing act of combating inflation with stimulus programmes while ensuring economic growth, “may keep a lid on valuations, squeezing exuberance out of the markets”.

However, banks risk ‘stagflation’ if they do not act, according to Ben Russon and Will Bradwell, fund managers at Franklin Templeton. This could occur in some markets next year if inflation rates exceed GDP growth.

Central banks have already started to act, but differ on their approaches. Below, Trustnet looks at how the three main central banks are tackling inflation in their regions in 2022.

Bank of England

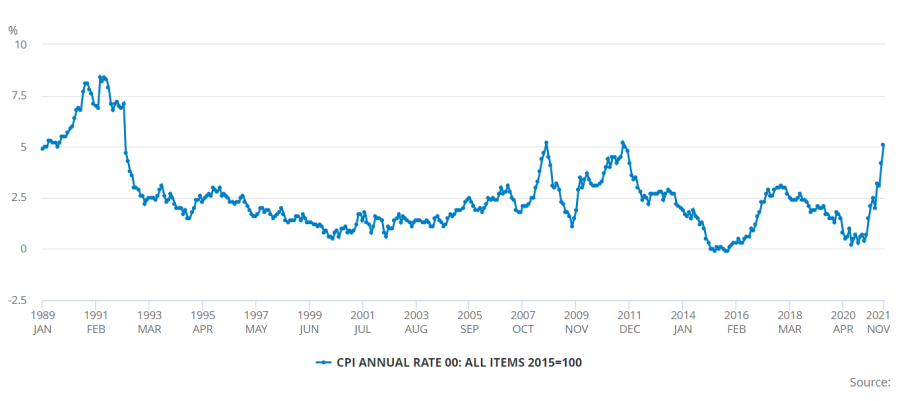

The Bank of England (BoE) rose interest rates to 0.25% after inflation rose to 5.1% in November, the highest it has reached in 10 years.

Changes to monetary policy are a rarity for the BofE, which has barely altered interest rates for much of the past decade, but the current inflation situation became too big to ignore.

David Roberts, head of the global fixed income team at Liontrust, said: “With RPI running at 7%, unemployment falling fast and fears that further lockdowns would only fuel further price rises, delaying rate hikes would surely have been a mistake.”

The bank has had to rethink its outlook after its original prediction that inflation would not reach 5% until spring next year was quickly shattered. New estimates anticipate that inflation in the UK will peak at 6% in April before easing.

UK CPI since 1989

Source: The Office for National Statistics

However the loaming threat of Omicron and stricter covid restrictions on the horizon could fast forward inflation again, leading to additional monetary tightening in the new year.

Slow GDP growth, which rose just 0.1% in November, made the bank hesitant to raise interest rates and stifle an already struggling economy. With a potential lockdown inbound, economic growth may slow down to the backdrop of rising inflation.

Laura Suter, head of personal finance at AJ Bell, said: “While Omicron is still a worry for the Bank, rampant inflation is clearly an even bigger concern.”

Federal Reserve

The US Federal Reserve (Fed) has taken one of the most aggressive strategies to combat inflation by tapering its bond purchasing programme.

The bank announced that it would be doubling its monthly tapering to $30bn (£22.5bn) after inflation in the US reached 6.8% in November, its highest level since 1991.

Ellen Gaske, lead economist, G10 economies on the global macroeconomic research team and Robert Tipp, chief investment strategist and head of global bonds at PGIM, said: “Fed officials are nervous inflation dynamics could take hold without more aggressive Fed action.”

After the tapering policy ends in March, Fed officials expect interest rates will be raised three times in 2022.

The Fed aims to reduce inflation rates to 2.6% by the end of next year through these monetary policies, but this may be overly optimistic, according to Kristina Hooper, chief global market strategist at Invesco.

She said: “We do think inflation could remain high — and even rise further — in coming months. However, our base case for 2022 expects the rate of increase to peak by mid-year as supply chain issues resolve, vaccination levels increase and more employees return to the workforce. So in the back half of 2022, we do not expect prices to continue to rise at a quickening pace.”

European Central Bank

The European Central Bank (ECB) also announced that it will be ending its Pandemic Emergency Purchase Plan in March 2021, but offset much of this by doubling the long running Asset Purchase Programme. It also gave no indication of an interest rate rise.

The bank is keeping its monetary policy flexible around the unpredictability of covid, not wanting to slow economic recovery as inflation rises.

Interest rates could potentially rise next year if inflation rates reach 2% ahead of its mid-year predictions, the bank says.

The ECB continues to describe the inflation problem as “transitory”, whereas the UK and US central banks are creating more long-term solutions, albeit with higher domestic inflation levels.