Funds focused on environmental, social and governance (ESG) principles have had a tough 2023, as political and economic shifts have moved the attention of investors elsewhere.

To show the depth of the malaise, the average trust in the IT Renewable Infrastructure sector is down 22.1% over the past 12 months.

In the US, there has been a pushback against the energy transition for different reasons, but in the UK the king’s speech last week has reinstated the government’s objective to attract “record levels of investment in renewable energy sources” and to “build on the United Kingdom’s track-record of decarbonising faster than other G7 economies”.

Below, James Smith, manager of the Premier Miton Global Renewables Trust, addresses the main concerns that have emerged around some sustainable solutions, including wind, hydrogen and electric vehicles (EVs), and tries to make some clarity around the efficacy of these technologies that have been under fire.

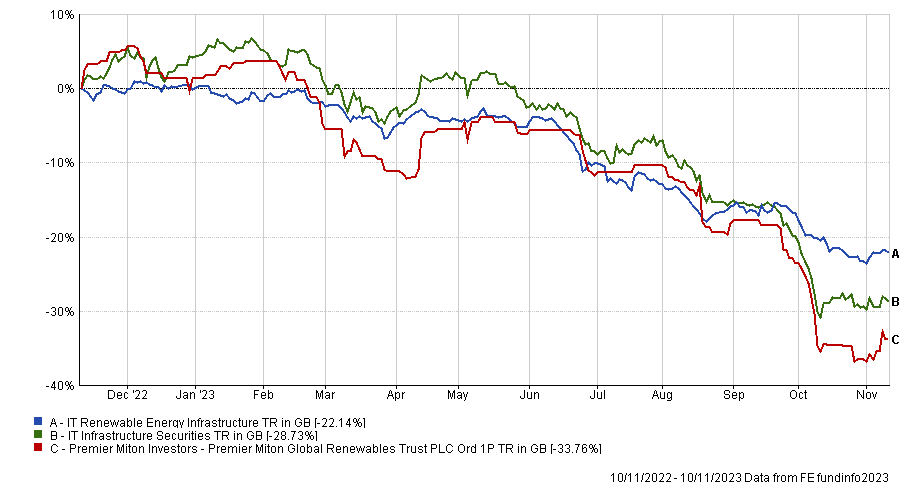

Despite the name, the trust sits in the IT Infrastructure Securities sector, which has performed slightly worse than the renewable peer group over the past year. The trust is down 33.8%, while its peer group has lost 28.7%, as the below chart shows.

Total return of trust vs sectors over 1yr

Source: FE Analytics

One of the main concerns around renewables has been around how solar and wind farms are energy- and land-intensive in the manufacturing process and only deliver intermittent power, the cost of which falls on the consumer.

Indeed it has “a certain cost” to manufacture renewable equipment, but most figures that Smith has access to indicate that the carbon emitted in their manufacture is repaid within three to six months of operation.

“So it isn’t that significant in the context of a 30 – 40 year life asset,” he said. “In terms of land, renewables are no barrier to farming, with wind typically being sited on either flat productive farmland or upland grazing. If anything, farmers like to farm on a wind farm as high-quality access roads are constructed for them by the renewable developer.”

Solar panels are usually situated on brownfield or low-grade farmland, as it does not make financial sense to turn grade one farmland into solar farms, so “the argument that we are going to run out of food due to solar really is ridiculous, to be polite”, said Smith.

Intermittency is an issue, he noted, but can be managed in several ways, such as the by reducing the costs of batteries – which have been getting cheaper – and balancing wind and solar output, which “show very strong negative correlation”.

“So having an energy system with large amounts of both works well in terms of reducing intermittency,” the manager said.

“Lastly, interconnections between countries are expanding, and this increases resiliency. It may be still in the UK, but windy in France. In future, Spain will generate substantial solar power reliably in summer, which is exported northward through Europe. In winter, offshore North Sea wind will generate more power than needed in the North, and will export the surplus south.”

Newer offshore wind farms are also more efficient and “massively reduce intermittency”.

Then, there is an economic argument. Do sustainable energies have a competitive advantage in relation to fossil fuels? Does it make sense to invest in them, given the subsidies that they need to survive? And can they provide cheaper energy per megawatt than oil and gas?

“In the past, renewables did need a subsidy but costs have fallen consistently. In addition, fossil fuel generation did not have to pay for carbon emissions, which they now do (so you could say fossil fuel generation was in the past subsidised by being relieved of this external cost),” said Smith.

“So in short, while renewable costs have been falling, fossil fuel generation costs have been increasing, and the two crossed a few years ago such that renewables are now cheaper than fossil fuel. Fossil generation costs have increased not only due to carbon costs but also the increasing cost of gas, which is now in the form of much higher priced [liquified natural gas] LNG rather than piped gas from Russia.”

The gas price also depends on the wholesale electricity market price in the UK and much of Europe, as gas is the highest marginal cost generator on the system (renewables have no marginal costs).

“Currently, wholesale electricity market price in the UK and Northern Europe is around £100-125 per megawatt-hour (MWh), while the cost of renewables is around £60 -70 per MWh for new build assets, slightly less for onshore wind and solar, slightly more for offshore.”

Also, according to Smith, dismissing the opportunity to invest in green energy because it is subsidised is shortsighted as “the human race would die out through global warming” if only reliant on coal and fossil fuels, as they would eventually run out.

Finally, for investors who believe that ESG investments only thrived in a low-interest-rates environment, the manager highlighted how the green stocks he owns in his investment trust are paying a dividend of between 5% and 10% and are very profitable, partly because they are selling power into an energy market dominated by higher cost technology such as gas.

“Other funds may be playing shorter term, macro or sector factors, for instance, selling or shorting ESG stocks that they believe (incorrectly in my opinion) are adversely affected by higher interest rates,” said Smith.

“Also general negativity to the sector arising from problems at sector leaders such as Orsted/NextEra Energy Partners might be playing a role in this, but I take perhaps a longer and more fundamental view than what may be characterised as ‘short money’,” he concluded.